Washington Metro

The Washington Metro, often abbreviated as the Metro and formally the Metrorail,[4] is a rapid transit system serving the Washington metropolitan area of the United States. It is administered by the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA), which also operates the Metrobus service under the Metro name.[5] Opened in 1976, the network now includes six lines, 98 stations, and 129 miles (208 km) of route.[6][7]

Metro serves Washington, D.C., as well as several jurisdictions in the states of Maryland and Virginia. In Maryland, Metro provides service to Montgomery and Prince George's counties; in Virginia, to Arlington, Fairfax and Loudoun counties, and to the independent city of Alexandria. The system's most recent expansion, which is the construction of a new station (and altering the line), serving Potomac Yard, opened on May 19, 2023. It operates mostly as a deep-level subway in more densely populated parts of the D.C. metropolitan area (including most of the District itself), while most of the suburban tracks are at surface level or elevated. The longest single-tier escalator in the Western Hemisphere, spanning 230 feet (70 m), is located at Metro's deep-level Wheaton station.[8]

In 2023, the system had a ridership of 136,303,200, or about 450,600 per weekday as of the third quarter of 2024, making it the second-busiest heavy rail rapid transit system in the United States, in number of passenger trips, after the New York City Subway, and the sixth-busiest in North America.[9] In June 2008, Metro set a monthly ridership record with 19,729,641 trips, or 798,456 per weekday.[10] Fares vary based on the distance traveled, the time of day, and the type of card used by the passenger. Riders enter and exit the system using a proximity card called SmarTrip.

History

[edit]

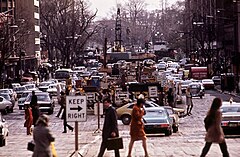

During the 1950s, plans were laid for a massive freeway system in Washington, D.C. Harland Bartholomew, who chaired the National Capital Planning Commission, thought that a rail transit system would never be self-sufficient because of low-density land uses and general transit ridership decline.[11] But the plan met fierce opposition, and was altered to include a Capital Beltway system plus rail line radials. The Beltway received full funding along with additional funding from the Inner Loop Freeway system project that was partially reallocated toward construction of the Metro system.[12]

In 1960, the federal government created the National Capital Transportation Agency to develop a rapid rail system.[13] In 1966, a bill creating WMATA was passed by the federal government, the District of Columbia, Virginia, and Maryland,[6] with planning power for the system being transferred to it from the NCTA.[14][15] An early proposal map from 1967 was more extensive than what was ultimately approved, with the Red Line's western terminus being in Germantown instead of Shady Grove.[16]

WMATA approved plans for a 97.2-mile (156.4 km) regional system on March 1, 1968. The plan consisted of a core regional system, which included the original five Metro lines, as well as several future extensions, many of which were not constructed.[17] The first experimental Metro station was built above ground in May 1968 for a cost of $69,000. It was 64 by 30 by 17 feet (19.5 m × 9.1 m × 5.2 m) and meant to test construction techniques, lighting, and acoustics before full-scale construction efforts.[18]

Construction began after a groundbreaking ceremony on December 9, 1969, when Secretary of Transportation John A. Volpe, District Mayor Walter Washington, and Maryland Governor Marvin Mandel tossed the first spade of dirt at Judiciary Square.[19]

The first portion of the system opened March 27, 1976, with 4.6 miles (7.4 km) available on the Red Line with five stations from Rhode Island Avenue to Farragut North, all in Washington, D.C.[20][21] All rides were free that day, with the first train departing the Rhode Island Avenue stop with Metro officials and special guests, and the second with members of the general public.[22] Arlington County, Virginia was linked to the system on July 1, 1977;[23] Montgomery County, Maryland, on February 6, 1978;[24] Prince George's County, Maryland, on November 17, 1978;[25] and Fairfax County, Virginia, and Alexandria, Virginia, on December 17, 1983.[6][26] Metro reached Loudoun County on November 15, 2022. Underground stations were built with cathedral-like arches of concrete, highlighted by soft, indirect lighting.[27] The name Metro was suggested by Massimo Vignelli, who designed the signage for the system as well as for the New York City Subway.[28]

The 103-mile (166 km), 83-station system was completed with the opening of the Green Line segment to Branch Avenue on January 13, 2001. However, this did not mean the end of the system's growth. A 3.22-mile (5.18 km) extension of the Blue Line to Morgan Boulevard and Downtown Largo opened on December 18, 2004. The first infill station, New York Ave–Florida Ave–Gallaudet University (now NoMa–Gallaudet U) on the Red Line between Union Station and Rhode Island Avenue, opened on November 20, 2004. Construction began in March 2009 for an extension to Dulles Airport to be built in two phases.[29] The first phase, five stations connecting East Falls Church to Tysons Corner and Wiehle Avenue in Reston, opened on July 26, 2014.[30] The second phase to Ashburn opened November 15, 2022, after many delays. The second infill station, Potomac Yard on the Blue and Yellow Lines between Braddock Road and National Airport, opened on May 19, 2023.[31]

Metro construction required billions of federal dollars, originally provided by Congress under the authority of the National Capital Transportation Act of 1969.[32] The cost was paid with 67% federal money and 33% local money. This act was amended on January 3, 1980, by the National Capital Transportation Amendment of 1979 (also known as the Stark-Harris Act),[33] which authorized additional funding of $1.7 billion to permit the completion of 89.5 miles (144.0 km) of the system as provided under the terms of a full funding grant agreement executed with WMATA in July 1986, which required 20% to be paid from local funds. On November 15, 1990, the National Capital Transportation Amendments of 1990[34] authorized an additional $1.3 billion in federal funds for construction of the remaining 13.5 miles (21.7 km) of the 103-mile (166 km) system, completed via the execution of full funding grant agreements, with a 63% federal/37% local matching ratio.[35]

In February 2006, Metro officials chose Randi Miller, a car dealership employee from Woodbridge, Virginia, to record new "doors opening", "doors closing", and "please stand clear of the doors, thank you" announcements after winning an open contest to replace the messages recorded by Sandy Carroll in 1996. The "Doors Closing" contest attracted 1,259 contestants from across the country.[36]

Over the years, a lack of investment in Metro caused it to break down, and there have been several fatal incidents on the Washington Metro due to mismanagement and broken-down infrastructure. By 2016, according to The Washington Post, on-time rates had dropped to 84%, and Metro service was frequently disrupted during rush hours because of a combination of equipment, rolling stock, track, and signal malfunctions.[37] WMATA did not receive dedicated funding from the three jurisdictions it served, Maryland, Virginia, and D.C., until 2018.[38]

Seeking to address negative perceptions of its performance, in 2016, WMATA announced an initiative called "Back2Good," focusing on addressing a wide array of rider concerns, from improving safety to adding Internet access to stations and train tunnels.[39]

In May 2018, Metro announced an extensive renovation of platforms at 20 stations across the system, spanning all lines except the Silver Line. The Blue and Yellow Lines south of National Airport were closed from May 25 to September 9, 2019, in what would be the longest line closure in Metro's history.[40][41] Additional stations would be repaired between 2020 and 2022, but the corresponding lines would not be closed completely. The project would cost $300 to $400 million and would be Metro's first major project since its construction.[42][43]

In March 2022, Metro announced that beginning on September 10, 2022, it would suspend all service on the Yellow Line for seven to eight months to complete repairs and rebuilding work on its bridge over the Potomac River and its tunnel leading into the station at L'Enfant Plaza.[44] Metro stated that this was the first significant work that the tunnel and bridge had undergone since they were first constructed over forty years prior.[44] Service on the Yellow Line resumed on May 7, 2023, but with its northeastern terminus truncated from Greenbelt to Mount Vernon Square.[45]

Opening dates

[edit]The following is a list of opening dates for track segments and infill stations on the Washington Metro. The entries in the "from" and "to" columns correspond to the boundaries of the extension or station that opened on the specified date, not to the lines' terminals.[8]: 3 [46]

| Date | Line at time of opening | Current lines | From | To | Stations | Miles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 27, 1976 | Red (service created) | Red | Farragut North | Rhode Island Avenue | 5 | 4.6 |

| December 15, 1976 | Red | Intermediate station (Gallery Place) | 1 | - | ||

| January 17, 1977 | Farragut North | Dupont Circle | 1 | 1.1 | ||

| July 1, 1977 | Blue (service created) | Blue, parts of Yellow, Orange, and Silver | National Airport | Stadium–Armory | 17 | 11.8 |

| February 4, 1978 | Red | Rhode Island Avenue–Brentwood | Silver Spring | 4 | 5.7 | |

| November 17, 1978[47] | Orange (service created) | Orange, part of Silver | Stadium–Armory | New Carrollton | 5 | 7.4 |

| December 1, 1979 | Orange | Orange and Silver | Rosslyn | Ballston–MU | 4 | 3.0 |

| November 22, 1980 | Blue | Blue and Silver | Stadium–Armory | Addison Road | 3 | 3.6 |

| December 5, 1981 | Red | Dupont Circle | Van Ness–UDC | 3 | 2.1 | |

| April 30, 1983 | Yellow (service created) | Yellow, part of Green | Gallery Place | Pentagon | 1 | 3.3 |

| December 17, 1983 | Yellow | Yellow, part of Blue | National Airport | Huntington | 4 | 4.2 |

| August 25, 1984 | Red | Van Ness–UDC | Grosvenor–Strathmore | 5 | 6.8 | |

| December 15, 1984 | Grosvenor–Strathmore | Shady Grove | 4 | 7.0 | ||

| June 7, 1986 | Orange | Ballston–MU | Vienna | 4 | 9.0 | |

| September 22, 1990 | Red | Silver Spring | Wheaton | 2 | 3.2 | |

| May 11, 1991 | Yellow | Yellow and Green | Gallery Place | U Street | 3 | 1.7 |

| June 15, 1991 | Blue | King Street–Old Town | Van Dorn Street | 1 | 3.9 | |

| December 28, 1991 | Green (service created) | Green | L'Enfant Plaza | Anacostia | 3 | 2.9 |

| December 11, 1993 | Green (separate segment) | Fort Totten | Greenbelt | 4 | 7.0 | |

| June 29, 1997 | Blue | Van Dorn Street | Franconia–Springfield | 1 | 3.3 | |

| July 25, 1998 | Red | Wheaton | Glenmont | 1 | 1.4 | |

| September 18, 1999 | Green (connecting segments) | Green | U Street | Fort Totten | 2 | 2.9 |

| January 13, 2001 | Green | Anacostia | Branch Avenue | 5 | 6.5 | |

| November 20, 2004 | Red | Infill station (NoMa–Gallaudet U) | 1 | - | ||

| December 18, 2004 | Blue | Blue and Silver | Addison Road | Downtown Largo | 2 | 3.2 |

| July 26, 2014 | Silver (service created) | Silver | East Falls Church | Wiehle–Reston East | 5 | 11.6 |

| November 15, 2022 | Silver | Wiehle–Reston East | Ashburn | 6 | 11.4 | |

| May 19, 2023 | Blue and Yellow | Infill station (Potomac Yard) | 1 | - | ||

Rush+ and late-night service patterns

[edit]

On December 31, 2006, an 18-month pilot program began to extend service on the Yellow Line to Fort Totten over existing Green Line trackage.[48][49] This extension was later made permanent.[50] Starting June 18, 2012, the Yellow Line was extended again along existing track as part of the Rush+ program, with an extension to Greenbelt on the northern end and with several trains diverted to Franconia–Springfield on the southern end. These Rush+ extensions were discontinued on June 25, 2017.[51]

In addition to expanding the system, Metro expanded the operating hours over the first 40 years. Though it originally opened with weekday-only service from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m, financial paperwork assumed prior to opening that it would eventually operate from 5 a.m. to 1 a.m. seven days a week. It never operated exactly on that schedule but the hours did expand, sometimes beyond that.[52] On September 25, 1978, Metro extended its weekday closing time from 8 p.m. to midnight and 5 days later it started Saturday service from 8 a.m. to Midnight.[53][54] Metrorail kicked off Sunday service from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. on September 2, 1979, and on June 29, 1986, the Sunday closing time was pushed back to midnight.[55] Metro started opening at 5:30 a.m., a half an hour earlier, on weekdays starting on July 1, 1988.[56] On November 5, 1999, weekend service was extended to 1:00 a.m., and on June 30, 2000, it was expanded to 2:00 a.m.[57][58] On July 5, 2003, weekend hours were extended again with the system opening an hour earlier, at 7:00 a.m. and closing an hour later at 3:00 a.m.[59] On September 27, 2004, Metro again pushed weekday opening time half an hour earlier, this time to 5 a.m.[60]

In 2016, Metro began temporarily scaling back service hours to allow for more maintenance. On June 3, 2016, they ended late-night weekend service with Metrorail closing at midnight.[61] Hours were adjusted again the following year starting on June 25, 2017, with weeknight service ending a half-hour earlier at 11:30 p.m.; Sunday service trimmed to start an hour later – at 8 a.m. – and end an hour early at 11 p.m.; and late-night service partially restored to 1 a.m. The service schedule was approved until June 2019.[62]

On January 29, 2020, Metro announced that it would be activating its pandemic response plans in preparation for the looming COVID-19 pandemic, which would be declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11. At that time, Metro announced that it would reduce its service hours from 5:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. on weekdays and 8:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. on weekends beginning on March 16 to accommodate for train cleaning and additional track work.[63] As of 2022, pre-COVID service hours have been restored with pre-2016 Sunday service hours.[64]

Busiest days

[edit]The highest ridership for a single day was on the day of the first inauguration of Barack Obama, January 20, 2009, with 1.12 million riders. It broke the previous record, set the day before, of 866,681 riders.[65] June 2008 set several ridership records: the single-month ridership record of 19,729,641 total riders, the record for highest average weekday ridership with 1,044,400 weekday trips, had five of the ten highest ridership days, and had 12 weekdays in which ridership exceed 800,000 trips.[10] The Sunday record of 616,324 trips was set on January 18, 2009, during Obama's pre-inaugural events, the day the Obamas arrived in Washington and hosted a concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. It broke the record set on the 4th of July, 1999.[66]

On January 21, 2017, the 2017 Women's March, set an all-time record in Saturday ridership with 1,001,616 trips.[67] The previous record was set on October 30, 2010, with 825,437 trips during the Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear.[68] Prior to 2010, the record had been set on June 8, 1991, at 786,358 trips during the Desert Storm rally.[69]

| Date | Trips | Event |

|---|---|---|

| January 20, 2009 | 1,120,000 | First inauguration of Barack Obama (Estimate) |

| January 21, 2017 | 1,001,613 | 2017 Women's March |

| April 2, 2010 | 891,240 | 2010 Cherry Blossom Festival/NBA Basketball |

| April 1, 2010 | 877,890 | 2010 Cherry Blossom Festival/NHL Hockey |

| April 10, 2013 | 871,432 | 2013 Cherry Blossom Festival/NBA Basketball/MLB Baseball |

| April 7, 2010 | 867,624 | 2010 Cherry Blossom Festival/MLB Baseball |

| January 19, 2009 | 866,681 | King Day of Service and Kid's Inaugural |

| June 8, 2010 | 856,578 | MLB Baseball – Stephen Strasburg debut |

| July 11, 2008 | 854,638 | MLB Baseball, Women of Faith Conference |

| April 8, 2010 | 852,103 | 2010 Cherry Blossom Festival/MLB Baseball/Stars on Ice |

Architecture

[edit]Many Metro stations were designed by Chicago architect Harry Weese and are examples of late 20th century modern architecture. With their heavy use of exposed concrete and repetitive design motifs, Metro stations display aspects of Brutalist design. The stations also reflect the influence of Washington's neoclassical architecture in their overarching coffered ceiling vaults. Weese worked with Cambridge, Massachusetts-based lighting designer Bill Lam on the indirect lighting used throughout the system.[72][73] All of Metro's original Brutalist stations are found in Downtown Washington, D.C., and neighboring urban corridors of Arlington, Virginia, while newer stations incorporate simplified cost-efficient designs.[74]

In 2007, the design of the Metro's vaulted-ceiling stations was voted number 106 on the "America's Favorite Architecture" list compiled by the American Institute of Architects (AIA), and was the only Brutalist design to win a place among the 150 selected by this public survey.[75]

In January 2014, the AIA announced that it would present its Twenty-five Year Award to the Washington Metro system for "an architectural design of enduring significance" that "has stood the test of time by embodying architectural excellence for 25 to 35 years". The announcement cited the key role of Weese, who conceived and implemented a "common design kit-of-parts", which continues to guide the construction of new Metro stations over a quarter-century later, albeit with designs modified slightly for cost reasons.[76]

Beginning in 2003, canopies were added to existing exits of underground stations due to the wear and tear seen on escalators due to exposure to the elements.[77]

-

Intersection of coffered concrete ceiling vaults at Metro Center (opened 1976), a major transfer station

-

Gallery Place station (opened 1976)

-

A train departs from McPherson Square station (opened 1977), which has an original ceiling vault design.

-

Van Ness–UDC (opened 1981) shows a modified ceiling vault.

-

Twinbrook station (opened 1984) is a typical original above-ground station.

-

King Street–Old Town (opened 1983) shows a modified elevated station design, used in historic Alexandria, as it was less intrusive.

-

The most recent elevated station design, seen at Wiehle–Reston East station, which opened in 2014, mirrors the design of the original underground stations.

-

Spring Hill (opened 2014) shows a modified version of the newest design, used on some elevated stations due to its cost savings.

-

The over-entrance canopy to L'Enfant Plaza (opened 1977) echoes the arched ceiling underground.

System

[edit]

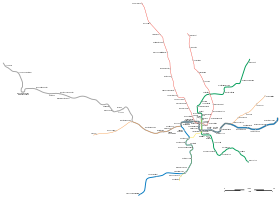

Since opening in 1976, the Metro network has grown to include six lines, 98 stations, and 129 miles (208 km) of route.[78] The rail network is designed according to a spoke–hub distribution paradigm, with rail lines running between downtown Washington and its nearby suburbs. The system extensively uses interlining: running more than one service on the same track. There are six operating lines.[78] The system's official map was designed by noted graphic designer Lance Wyman[79] and Bill Cannan while they were partners in the design firm of Wyman & Cannan in New York City.[80]

About 50 miles (80 km) of Metro's track is underground, as are 47 of the 98 stations. Track runs underground mostly within the District and high-density suburbs. Surface track accounts for about 46 miles (74 km) of the total, and aerial track makes up 9 miles (14 km).[78] The system operates on a track gauge of 4 ft 8+1⁄4 in (1,429 mm), which is 1⁄4 inch (6.4 mm) narrower than 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge but within the tolerance of standard-gauge railways.[81]

Previously, the least time to travel through 97 stations using only mass transit was 8 hours 54 minutes, a record set by travel blogger Lucas Wall on November 16, 2022, the first full day that Phase 2 of the Silver Line was in passenger operation.[82] This record was broken by a student named Claire Aguayo, who did it in 8 hours and 36 minutes on January 23, 2023.[83] Both of these runs were before the Potomac Yard station opened on May 19, 2023, making them no longer current.

To gain revenues, WMATA has started to allow retail ventures in Metro stations. WMATA has authorized DVD-rental vending machines and ticket booths for the Old Town Trolley Tours and is seeking additional retail tenants.[84]

| Line Name | Service Introduced | Stations | Distance | Termini | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mi | km | Western/Southern | Eastern/Northern | ||||

| March 29, 1976 | 27 | 31.9 | 51.3 | Shady Grove | Glenmont | ||

| November 20, 1978 | 26 | 26.4 | 42.5 | Vienna | New Carrollton | ||

| July 1, 1977 | 28 | 30.3 | 48.8 | Franconia–Springfield | Largo | ||

| December 28, 1991 | 21 | 23.0 | 37.0 | Branch Avenue | Greenbelt | ||

| March 30, 1983 | 13 | 10.7 | 17.2 | Huntington | Mount Vernon Square | ||

| July 26, 2014 | 34 | 41.1 | 66.1 | Ashburn | Largo | ||

| Line Name | Service Introduced | Service Discontinued | Stations | Termini | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western/Southern | Eastern/Northern | ||||||

| December 15, 1984 | December 16, 2018 | 20 | Grosvenor–Strathmore | Silver Spring | Grosvenor Turnback ended in December 2018, Silver Spring Turnback ended in July 2019 | ||

| December 19, 1993 | September 17, 1999 | 5 | Fort Totten | Greenbelt | Only operated during off-peak hours and weekends starting on January 27, 1997. Discontinued at the opening of the Green Line segment between Fort Totten and U Street in 1999. | ||

| January 27, 1997 | September 17, 1999 | 11 | Farragut North | Greenbelt | Only operated during peak hours. Discontinued at the opening of the Green Line segment between Fort Totten and U Street in 1999. | ||

| April 20, 2006 | May 24, 2019 | 17 | Huntington | Fort Totten | Only operated during off-peak hours and weekends. | ||

| June 18, 2012 | June 24, 2017 | 21 | Franconia-Springfield | Greenbelt | Only operated during peak hours. | ||

| June 18, 2012 | July 25, 2014 | 26 | Vienna | Downtown Largo | Only operated during peak hours. Discontinued at the introduction of Silver Line service in 2014. | ||

Financing

[edit]Metro relies extensively on passenger fares and appropriated financing from the Maryland, Virginia, and Washington D.C., governments, which are represented on Metro's board of directors. In 2018, Maryland, Virginia and Washington, D.C., agreed to contribute $500 million annually to Metro's capital budget.[38] Until then, the system did not have a dedicated revenue stream as other cities' mass transit systems do. Critics allege that this has contributed to Metro's recent history of maintenance and safety problems.[86][37]

For Fiscal Year 2019, the estimated farebox recovery ratio (fare revenue divided by operating expenses) was 62 percent, based on the WMATA-approved budget.[87]

Infrastructure

[edit]Stations

[edit]

There are 40 stations in the District of Columbia, 15 in Prince George's County, 13 in Fairfax County, 11 in Montgomery County, 11 in Arlington County, 5 in the City of Alexandria, and 3 in Loudoun County.[78] The most recent station was opened on May 19, 2023, an infill station at Potomac Yard.[31] At 196 feet (60 m) below the surface, the Forest Glen station on the Red Line is the deepest in the system. There are no escalators; high-speed elevators take 20 seconds to travel from the street to the station platform. The Wheaton station, one stop to the north of the Forest Glen station, has the longest continuous escalator in the US and in the Western Hemisphere, at 230 feet (70 m).[78][88] The Rosslyn station is the deepest station on the Orange/Blue/Silver Line, at 117 feet (36 m) below street level. The station features the second-longest continuous escalator in the Metro system at 194 feet (59 m); an escalator ride between the street and mezzanine levels takes nearly two minutes.[89]

The system is not centered on any single station, but Metro Center is at the intersection of the Red, Orange, Blue, and Silver Lines.[90] The station is also the location of WMATA's main sales office, which closed in 2022. Metro has designated five other "core stations" that have high passenger volume, including:[91] Gallery Place, transfer station for the Red, Green, and Yellow Lines; L'Enfant Plaza, transfer station for the Orange, Blue, Silver, Green, and Yellow Lines; Union Station, the busiest station by passenger boardings;[90] Farragut North; and Farragut West.

To deal with the high number of passengers in transfer stations, Metro is studying the possibility of building pedestrian connections between nearby core transfer stations. For example, a 750-foot (230 m) passage between Metro Center and Gallery Place stations would allow passengers to transfer between the Orange/Blue/Silver and Yellow/Green Lines without going to one stop on the Red Line or taking a slight detour via L’Enfant Plaza. Another tunnel between Farragut West and Farragut North stations would allow transfers between the Red and Orange/Blue/Silver lines, decreasing transfer demand at Metro Center by an estimated 11%.[91] The Farragut pedestrian tunnel has yet to be physically implemented, but was added in virtual form effective October 28, 2011: the SmarTrip system now interprets an exit from one Farragut station and entrance to the other as part of a single trip, allowing cardholders to transfer on foot without having to pay a second full fare.[92]

| Rank | Station | Entries | Line(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Metro Center | 3,929,940 | |

| 2 | Foggy Bottom–GWU | 3,742,176 | |

| 3 | Union Station | 3,651,760 | |

| 4 | Gallery Place | 3,536,641 | |

| 5 | Dupont Circle | 2,985,099 | |

| 6 | Farragut North | 2,779,479 | |

| 7 | L'Enfant Plaza | 2,739,674 | |

| 8 | Farragut West | 2,616,830 | |

| 9 | NoMa–Gallaudet U | 2,406,409 | |

| 10 | Navy Yard–Ballpark | 2,310,236 |

Rolling stock

[edit]Metro's fleet consists of 1,216 rail cars, each 75 feet (22.86 m) long, with 1,208 in active revenue service as of May 2024. Though operating rules currently limit trains to 59 mph (95 km/h) (except on the Green line, where they can go up to 65 mph (105 km/h)),[94] all trains have a maximum speed of 75 mph (121 km/h), and average 33 mph (53 km/h), including stops.[78] All cars operate as married pairs (consecutively numbered even-odd with a cab at each end of the pair except 7000-series railcars), with systems shared across the pair.[95]

In the "Active railcars" table, font in bold represents the railcars that are currently in service, while the regular font represents cars that are temporarily out of service

| Active railcars | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Series | Manufacturer | Number purchased[96] | Entered service | Retired (estimated) | Currently owned[96] | Currently active[96] | Planned replacement | ||

| 3000 | Breda | 290 | 1987 | 2027–2029 | 284 | 280 | 8000-series | ||

| 6000 | Alstom | 184 | 2006 | 184 | 180 (additional 2 for "money train") |

||||

| 7000 | Kawasaki | 748 | 2015 | 748 | 748 | ||||

| Retired railcars | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Series | Manufacturer | Number purchased[96] | Entered service | Retired | Currently owned[96] | Replacement | |||

| 1000 | Rohr | 300 | 1976 | 2016–2017 | 2 preserved[97] | 7000-series | |||

| 2000 | Breda | 76 | 1982 | 2024 | 2 preserved | 8000-series | |||

| 4000 | 100 | 1991 | 2017[98] | 2 preserved[99][100] | 7000-series | ||||

| 5000 | CAF / AAI | 192 | 2001 | 2018–2019[101] | 2 preserved | 7000-series | |||

| Future railcars | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Series | Manufacturer | Number purchased[96] | Entered service (estimated) | ||||||

| 8000 | Hitachi[102] | 256–800[103] (proposed) | 2027[103] | ||||||

Metro's rolling stock was acquired in seven phases, and each version of car is identified with a separate series number.

The original order of 300 railcars (all of which have been retired as of July 1, 2017)[100] was manufactured by Rohr Industries, with final delivery in 1978.[104] These cars are numbered 1000–1299 and were rehabilitated in the mid-1990s.

Breda Costruzioni Ferroviarie (Breda), manufactured the second order of 76 cars delivered in 1983 and 1984.[104] These cars, numbered 2000–2075, were rehabilitated in the early 2000s by Alstom in Hornell, New York.[105] All 2000-series cars were retired by May 10, 2024.[106]

A third order of 290 cars, also from Breda, were delivered between 1984 and 1988.[104] These cars are numbered 3000–3289 and were rehabilitated by Alstom in the mid-2000s.[105]

A fourth order of 100 cars from Breda, numbered 4000–4099, were delivered between 1991 and 1994.[104] All 4000-series cars were retired by July 1, 2017.[98]

A fifth order of 192 cars was manufactured by Construcciones y Auxiliar de Ferrocarriles (CAF) of Spain. These cars are numbered 5000–5191 and were delivered from 2001 through 2004.[104] Most 5000-series cars were retired in October 2018 and the last few in spring 2019.[101]

A sixth order of 184 cars from Alstom Transportation, are numbered 6000–6183 and were delivered between 2005 and 2007.[104] The cars have body shells built in Barcelona, Spain with assembly completed in Hornell, New York.[107]

The 7000-series railcars, built by Kawasaki Heavy Industries Rolling Stock Company of Kobe, Japan, were delivered for on-site testing during winter 2013–2014, and first entered service on April 14, 2015, on the Blue Line. The cars are different from previous models in that while still operating as married pairs, the cab in one car is eliminated, turning it into a B car. This design allows for increased passenger capacity, elimination of redundant equipment, greater energy efficiency, and lower maintenance costs. The National Transportation Safety Board investigation of the fatal June 22, 2009, accident led it to conclude that the 1000-series cars are unsafe and unable to protect passengers in a crash. As a result, on July 26, 2010, Metro voted to purchase 300 7000-series cars, which replaced the remaining 1000-series cars.[108][109] An additional 128 7000-series cars were also ordered to serve the Silver Line to Dulles Airport (64 for each phase). In April 2013, Metro placed another order for 100 7000-series cars, which replaced all of the 4000-series cars.[110] On July 13, 2015, WMATA used their final option and purchased an additional 220 7000-series railcars for fleet expansion and to replace the 5000-series railcars, bringing the total order number to 748 railcars. On February 26, 2020, WMATA accepted the delivery of the final 7000-series car.[111]

The 8000-series cars will be constructed by Hitachi Rail.[112][113] While these railcars would have a similar appearance to the 7000-series, the 8000-series would include more features such as "smart doors" that detect obstruction, high-definition security cameras, more space between seats, wider aisles, and non-slip flooring.[113] In September 2018, Metro issued a request for proposals from manufacturers for 256 railcars with options for a total of up to 800.[114] The first order would replace the 2000 and 3000-series equipment, while the options, if selected, would allow the agency to increase capacity and retire the 6000-series.[114]

Signaling and operation

[edit]During normal passenger operation on revenue tracks, trains are designed to be controlled by an integrated Automatic Train Operation (ATO) and Automatic Train Control (ATC) system that accelerates and brakes trains automatically without operator intervention. All trains are still staffed with train operators who open and close the doors, make station announcements, and supervise their trains. The system was designed so that an operator could manually operate a train when necessary.[115]

Since June 2009, when two Red Line trains collided and killed nine people due in part to malfunctions in the ATC system, all Metro trains have been manually operated.[116] The current state of manual operation has led to heavily degraded service, with new manual requirements such as absolute blocks, speed restrictions, and end-of-platform stopping leading to increased headways between trains, increased dwell time, and worse on-time performance.[117] Metro originally planned to have all trains be automated again by 2017,[118] but those plans were shelved in early 2017 in order to focus on more pressing safety and infrastructure issues.[119] In March 2023, Metro announced plans to re-automate the system by December of that year,[120] but announced in September that these plans would be delayed until 2024.[121]

The train doors were originally designed to be opened and closed automatically and the doors would re-open if an object blocked them, much as elevator doors do. Almost immediately after the system opened in 1976 Metro realized these features were not conducive to safe or efficient operation and they were disabled. Metro began testing reinstating automatic train door opening in March 2019, citing delays and potential human error.[122] If a door tries to close and it meets an obstruction, the operator must re-open the door. In October 2023, automatic train door opening, where train doors will automatically open upon alighting, was restored to a limited number of trains on the Red Line. Operators must manually close the doors after they open. WMATA claims that automatic door opening provides a safety benefit since it eliminates potential human error resulting in the doors opening on the wrong side and a reduction in the wait time before doors opening, improving the customer experience and station dwell times.[123]

Hours and headways

[edit]

Metrorail begins service at 5 am Monday through Friday, 7 am on Saturdays and Sundays; it ends service at midnight Monday through Thursday, 1:00 am Friday and Saturday, and midnight on Sundays, although the last trains leave the end stations inbound about half an hour before these times.[124][125] Pre-pandemic, trains ran more frequently during rush hours on all lines, with scheduled peak hour headways of 4 minutes on the Red Line and 8 minutes on all other lines. Headways were much longer during midday and evening on weekdays and all day weekends. The midday six-minute headways were based on a combination of two Metrorail lines (Orange/Blue and Yellow/Green) as each route could run every 12 minutes; in the case of the Red Line, every other train bound for Glenmont terminated at Silver Spring instead. Night and weekend service varied between 8 and 20 minutes, with trains generally scheduled only every 15 to 20 minutes.[126]

Other service truncations also occur in the system during rush hour service only. On the Red Line, every other train bound for Shady Grove terminated at Grosvenor–Strathmore until December 2018,[127] in addition to the alternating terminations at Silver Spring mentioned above. For the Yellow Line, all non Rush+ trains bound for Greenbelt and all normal trains bound for Fort Totten terminate at Mount Vernon Square. These are primarily instituted due to a limited supply of rail cars and the locations of pocket tracks throughout the system. However, as of July 2019, both Red Line service truncations have ended, and as of April 2019, the Yellow Line served Greenbelt at all times. When the Yellow Line reopened on May 7, 2023, following major maintenance work, the Mount Vernon Square turnback was reinstated at all times, which has not happened since 2006.

Until 1999, Metro ended service at midnight every night, and weekend service began at 8 am. That year, WMATA began late-night service on Fridays and Saturdays until 1 am. By 2007, with encouragement from businesses, that closing time had been pushed back to 3 am,[128] with peak fares in effect for entries after midnight. There were plans floated to end late-night service due to costs in 2011, but they were met with resistance by riders.[129] WMATA temporarily discontinued late night rail service on May 30, 2016, so that Metro can conduct an extensive track rehabilitation program in an effort to improve the system's reliability.[130][131]

On June 25, 2017, Metro cut its hours of operation with closing at 11:30 PM Monday–Thursday, 1 AM on Friday and Saturday, and 11 PM on Sunday,[132][133] with the last trains leaving the end stations inbound about half an hour before these times.[134] As of 2022, the pre-2017 service hours have been restored.[64]

Special service patterns

[edit]Metro runs special service patterns on holidays and when events in Washington may require additional service. Independence Day activities require Metro to adjust service to provide extra capacity to and from the National Mall.[135] WMATA makes similar adjustments during other events, such as presidential inaugurations. Due to security concerns related to the January 6 United States Capitol attack, several Metro stations were closed for the 2021 Inauguration. Metro has altered service and used some stations as entrances or exits only to help manage congestion.[136]

Rush Plus

[edit]In 2012, WMATA announced enhanced rush period service that was implemented on June 18, 2012, under the name "Rush+" (or "Rush Plus"). Rush Plus service occurred only during portions of peak service: 6:30–9:00 AM and 3:30–6:00 PM, Monday through Friday.

The Rush+ realignment was intended to free up space in the Rosslyn Portal (the tunnel between Rosslyn and Foggy Bottom), which operates at full capacity already. When Silver Line service began, those trains would be routed through the tunnel, and so some of what were Blue Line trains to Largo were now diverted across the Fenwick Bridge to become Yellow Line trains running all the way along the Green Line to Greenbelt. Select Yellow Line trains running south diverted along the Blue Line to Franconia–Springfield (as opposed to the normal Yellow line terminus at Huntington). Until the start of Silver Line service, excess Rosslyn Tunnel capacity was used by additional Orange Line trains that traveled along the Blue Line to Largo (as opposed to the normal Orange Line terminus at New Carrollton). Rush+ had the additional effect of giving some further number of passengers transfer-free journeys, though severely increasing headways for the portion of the Blue Line running between Pentagon and Rosslyn. In May 2017, Metro announced that Yellow Rush+ service would be eliminated effective June 25, 2017.[137]

COVID-19 and 7000-series derailment (2020–present)

[edit]Headways have been lengthened as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in Washington, D.C., starting early 2020. Near-pre-pandemic service was restored at times until October 2021, but due to the 7000-series derailment near Arlington Cemetery, and subsequent removal of all 7000-series cars from service (which made up 60% of the WMATA fleet), headways were lengthened again to every 15 minutes on the Red Line and every 30 minutes on all other lines beginning October 19, 2021.[138]

Since then, with more 7000-series cars returning, headways have been gradually restored to near-pre-pandemic levels, especially outside of peak times, with ridership also increasing as a result. As of September 2024, several lines are actually more frequent than 2019 levels during certain times of day on weekdays and/or weekends. The Red Line's evening headways improved from every 15 minutes in 2019 to every 10 minutes in 2024. In 2019, all lines except the Red Line had 20-minute evening headways, whereas in 2024 the Green and Yellow Lines run every 8 minutes during evenings and the Blue, Orange, and Silver Lines every 15. Sunday service improved to match Monday-Friday off-peak and Saturday levels of every 6 minutes on the Red Line, every 8 minutes on the Green and Yellow Lines, and every 12 minutes on the Blue, Orange, and Silver Lines, compared to the previous 8 minutes on the Red Line and 15 minutes on all other lines. The Yellow and Green Lines also currently run every 6 minutes during rush hours starting 2023 for the first time since major peak service cuts in 2017 that eliminated Rush Plus and decreased rush hour frequencies on all lines except the Blue Line from 6 to 8 minutes.

Current headways by line

[edit]Headways as of September 1, 2024.[139]

| Line(s) | Weekdays | Weekends | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak (7am–9am, 4pm–6pm) | Off-peak (all other times) | Late night (9:30pm–close) | Daytime (7am–9:30pm) | Late night (9:30pm–close) | |

| 5 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 10 | |

| 6 | 8 | ||||

| 10 | 12 | 15 | 12 | 15 | |

Current average headways by line segment

[edit]Headways as of November 9, 2024. Calculated using trains per hour and rounded to nearest minute.[139]

| Section | Line(s) | Weekday rush (7–9am, 4–6pm) | Off-peak (before 9:30pm) | Late Night (9:30pm–close) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shady Grove – Glenmont | 5 | 6 | 10 | |

| Branch Avenue – L'Enfant Plaza | 6 | 8 | ||

| Huntington – King Street–Old Town | 6 | 8 | ||

| L'Enfant Plaza – Mount Vernon Square | 3 | 4 | ||

| Mount Vernon Square – Greenbelt | 6 | 8 | ||

| Franconia–Springfield – King Street–Old Town | 10 | 12 | 15 | |

| King Street–Old Town – Pentagon | 4 | 5 | ||

| Pentagon – Rosslyn | 10 | 12 | 15 | |

| Vienna – East Falls Church | 10 | 12 | 15 | |

| Ashburn – East Falls Church | 10 | 12 | 15 | |

| East Falls Church – Rosslyn | 5 | 6 | 8 | |

| Rosslyn – Stadium–Armory | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Stadium–Armory – Downtown Largo | 5 | 6 | 8 | |

| Stadium–Armory – New Carrollton | 10 | 12 | 15 | |

Passenger information systems

[edit]

A passenger information display system (PIDS) was installed in all Metrorail stations in 2000. Displays are located on all track platforms and at the mezzanine entrances of stations. They provide real-time information on next train arrivals, including the line, destination, number of cars in the train, and estimated wait time. The displays also show information about delayed trains, emergency announcements, and other bulletins.[140] The signs were upgraded in 2013 to better reflect Rush Plus and Silver Line schedules, and to prioritize next-train arrival information over other announcements.[141] New digital PIDS signs were installed at the six stations south of National Airport in summer 2019 as part of the Platform Improvement Project.[142]

WMATA also provides current train and related information to customers with conventional web browsers, as well as users of smartphones and other mobile devices.[143] In 2010 Metro began sharing its PIDS data with outside software developers, for use in creating additional real-time applications for mobile devices. Free apps are available to the public on major mobile device software platforms (iOS, Android, Windows Phone, Palm).[144][145] WMATA also began providing real-time train information by phone in 2010.[146]

Fare structure

[edit]

Riders enter and exit the system using a stored-value card in the form of a proximity card known as SmarTrip. The fare is deducted from the balance of the card when exiting.[147] SmarTrip cards can be purchased at station vending machines, online or at retail outlets, and can store up to $300 in value. Metro also accepts Baltimore's CharmCard, a similar contactless payment card system.

Metro fares vary based on the distance traveled and the time of day at entry. Fares (effective 2024) range from $2.25 to $6.75, depending on the distance traveled during weekdays prior to 9:30 PM and $2.25 to $2.50 on weekends or after 9:30 PM on weekdays at the time of tapping in. Discounted fares from 50% to 100% are available for DC school children,[148] SNAP Recipients in Maryland, Virginia, and Washington DC,[149] people with disabilities,[150][151] and senior citizens.[151] Parking fees at Metro stations range from $3.00 to $5.20 on weekdays for riders; non-rider fees range from $3.00 to $10.00. Parking is free on Saturdays, Sundays, and federal holidays.[152]

Since June 25, 2017, the first fare hike in three years, peak-period rail fares increased 10 cents, with $2.25 as the new minimum and $6.00 as the maximum one-way fare. Off-peak fares rose 25 cents, to a $2.00 minimum and $3.85 maximum, as will bus fares.[153][154][155][133] A new one-day unlimited rail / bus pass became available for $14.75,[133] which is presently available for $13.50.[156]

On June 24, 2024, WMATA announced another fare hike effective June 30, 2024, with a general increase of 12.5% to most services. Of the fare increases, the rail fare during the weekday increased to range from $2.25 to $6.75, while the flat $2.00 rate during late night (after 9:30) and weekend hours was replaced to range from $2.25 to $2.50 depending on the distance traveled.[157]

Passengers may purchase passes at farecard vending machines. Passes are loaded onto the same SmarTrip cards as stored value, but grant riders unlimited travel within the system for a certain period of time. The period of validity starts with the first use. Four types of passes are currently sold:[156][158]

- A 1-Day Unlimited Pass for $13.50, valid for one day of unlimited Metrorail and Metrobus travel. The pass expires at the end of the operating day.

- A 3-Day Unlimited Pass for $33.75, valid for three consecutive days of unlimited Metrorail and Metrobus travel.

- A 7-Day Short Trip Unlimited Pass for $40.50, valid for seven consecutive days for Metrorail trips costing up to $4.50. If the trip costs more than $4.50, the difference is deducted from the cash balance of a SmarTrip card, possibly after the necessary value is added at the Exitfare machine. A non-negative stored value is required to enter and exit the Metrorail system.

- A 7-Day Unlimited Pass for $60.75, valid for seven consecutive days of unlimited Metrorail and Metrobus travel.

In addition, Metro sells the Monthly Unlimited Pass, formerly called SelectPass, available for purchase online only by registered SmarTrip cardholders, valid for trips up to a specified value for a specific calendar month, with the balance being deducted from the card's cash value similarly to the Short Trip Pass.[159] The pass is priced based on 18 days of round-trip travel.[160]

Users can add value to any farecard. Riders pay an exit fare based on time of day and distance traveled. Trips may include segments on multiple lines under one fare as long as the rider does not exit the faregates, with the exception of the "Farragut Crossing" out-of-station interchange between the Farragut West and Farragut North stations. At Farragut Crossing, riders may exit from one station and reenter at the other within 30 minutes on a single fare. When making a trip that uses Metrobus and Metrorail, a $2.25 discount is available when using a SmarTrip card when transferring from Metrobus to Metrorail, and Transfers from Metrorail to Metrobus are free; Transfers must be done within 2 hours.[161][92] When entering and exiting at the same station, users are normally charged a minimum fare ($2.25). However, since July 1, 2016, users have had a 15-minute grace period to exit the station; those who do so will receive a rebate of the amount paid as an autoload to their SmarTrip card.[162][163]

Students at District of Columbia schools (public, charter, private, and parochial) ride both Metrobus and Metrorail for free.[164]

Fare history

[edit]

The contract for Metro's fare collection system was awarded in 1975 to Cubic Transportation Systems.[165] Electronic fare collection using paper magnetic stripe cards started on July 1, 1977, a little more than a year after the first stations opened. Prior to electronic fare collection, exact change fareboxes were used.[166] Metro's historic paper farecard system is also shared by Bay Area Rapid Transit, which Cubic won a contract for in 1974.[165] Any remaining value stored on the paper cards was printed on the card at each exit, and passes were printed with the expiration date.

Several adjustments were made to shift the availability of passes from paper tickets to SmarTrip cards in 2012 and 2013. In May 2014 Metro announced plans to retrofit more than 500 fare vending machines throughout the system to dispense SmarTrip cards, rather than paper fare cards, and eventually eliminate magnetic fare cards entirely.[167] This was completed in early December 2015 when the last paper farecard was sold.[168] The faregates stopped accepting paper farecards on March 6, 2016,[169][170] and the last day for trading in farecards to transfer the value to SmarTrip was June 30, 2016.[170]

Safety and security

[edit]Security

[edit]

Metro planners designed the system with passenger safety and order maintenance as primary considerations. The open vaulted ceiling design of stations and the limited obstructions on platforms allow few opportunities to conceal criminal activity. Station platforms are built away from station walls to limit vandalism and provide for diffused lighting of the station from recessed lights. Metro's attempts to reduce crime, combined with how the station environments were designed with crime prevention in mind,[171] have contributed to Metro being among the safest and cleanest subway systems in the United States.[172] There are nearly 6,000 video surveillance cameras used across the system to enhance security.[173]

Metro is patrolled by its own police force, which is charged with ensuring the safety of passengers and employees. Transit Police officers patrol the Metro and Metrobus systems, and they have jurisdiction and arrest powers throughout the 1,500-square-mile (3,900 km2) Metro service area for crimes that occur on or against transit authority facilities, or within 150 feet (46 m) of a Metrobus stop. The Metro Transit Police Department is one of two U.S. police agencies that has local police authority in three "state"-level jurisdictions (Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia), the U.S. Park Police being the other.[174]

Each city and county in the Metro service area has similar ordinances that regulate or prohibit vending on Metro-owned property, and which prohibit riders from eating, drinking, or smoking in Metro trains, buses, and stations; the Transit Police have a reputation for enforcing these laws rigorously. One widely publicized incident occurred in October 2000 when police arrested 12-year-old Ansche Hedgepeth for eating french fries in the Tenleytown–AU station.[175] In a 2004 opinion by John Roberts, now Chief Justice of the United States, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Hedgepeth's arrest.[176] By then WMATA had answered negative publicity by adopting a policy of first issuing warnings to juveniles, and arresting them only after three violations within a year.

Metro's zero tolerance policy on food, trash and other sources of disorder embodies the "broken windows" philosophy of crime reduction. This philosophy also extends to the use of station restroom facilities. A longstanding policy, intended to curb unlawful and unwanted activity, has been to only allow employees to use Metro restrooms.[172] One widely publicized example of this was when a pregnant woman was denied access to the bathroom by a station manager at the Shady Grove station.[177] Metro now allows the use of restrooms by passengers who gain a station manager's permission, except during periods of heightened terror alerts.[178][179]

On January 22, 2019, the D.C. Council voted 11–2 to override Mayor Muriel Bowser's veto of the Fare Evasion Decriminalization Act, setting the penalty for fare evasion at a $50 civil fine, a reduction from the previous criminal penalty of a fine up to $300 and 10 days in jail.[180]

Random bag searches

[edit]On October 27, 2008, the Metro Transit Police Department announced plans to immediately begin random searches of backpacks, purses, and other bags. Transit police would search riders at random before boarding a bus or entering a station. It also explained its intent to stop anyone acting suspiciously.[181] Metro claims that "Legal authority to inspect packages brought into the Metro system has been established by the court system on similar types of inspections in mass transit properties, airports, military facilities and courthouses."[182] Metro Transit Police Chief Michael Taborn stated that, if someone were to turn around and simply enter the system through another escalator or elevator, Metro has "a plan to address suspicious behavior".[183] Security expert Bruce Schneier characterized the plan as "security theater against a movie plot threat" and does not believe random bag searches actually improve security.[184]

The Metro Riders' Advisory Council recommended to WMATA's board of directors that Metro hold at least one public meeting regarding the search program. As of December 2008[update], Metro had not conducted a single bag search.[185]

In 2010 Metro once again announced that it would implement random bag searches, and conducted the first such searches on December 21, 2010.[186] The searches consist of swabbing bags and packages for explosive residue, and X-raying or opening any packages which turned up positive. On the first day of searches, at least one false positive for explosives was produced, which Metro officials indicated could occur for a variety of reasons including if a passenger had recently been in contact with firearms or been to a firing range.[187] The D.C. Bill of Rights Coalition and the Montgomery County Civil Rights Coalition circulated a petition against random bag searches, taking the position that the practice violates the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution and would not improve security.[188] On January 3, 2011, Metro held a public forum for the searches at a Metro Riders' Advisory Council meeting, at which more than 50 riders spoke out, most of them in opposition to the searches. However at the meeting Metro officials called random bag inspections a "success" and claimed that few riders had complained.[189]

After a prolonged absence, as of February 2017[update], bag searches have resumed at random stations throughout the Washington Metro area.[citation needed]

Safety

[edit]Accidents and incidents

[edit]Several collisions have occurred on Washington Metro, resulting in injuries and fatalities, along with numerous derailments with few or no injuries. WMATA has been criticized for disregarding safety warnings and advice from experts. The Tri-State Oversight Committee oversaw WMATA, but had no regulatory authority. Metro's safety department is usually in charge of investigating incidents, but could not require other Metro departments to implement its recommendations.[190] Following several safety lapses, the Federal Transit Administration assumed oversight at WMATA.[191]

Collisions

[edit]

During the Blizzard of 1996, on January 6, a Metro operator was killed when a train failed to stop at the Shady Grove station. The four-car train overran the station platform and struck an unoccupied train that was awaiting assignment. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigation found that the crash was a result of a failure in the train's computer-controlled braking system. The NTSB recommended that Metro grant train operators the ability to manually control the braking system, even in inclement weather, and recommended that Metro prohibit parked rail cars on tracks used by incoming outbound trains.[192]

On November 3, 2004, an out-of-service Red Line train rolled backwards into the Woodley Park station, hitting an in-service train stopped at the platform. The rear car (1077) was telescoped by the first car of the standing train (4018). No one died, 20 people were injured.[193] A 14-month investigation concluded that the train operator was most likely not alert as the train rolled backwards into the station. Safety officials estimated that had the train been full, at least 79 people would have died. The train operator was dismissed and Metro officials agreed to add rollback protection to more than 300 rail cars.[194]

On June 22, 2009, at 5:02 pm, two trains on the Red Line collided. A southbound train heading toward Shady Grove stopped on the track short of the Fort Totten station and another southbound train collided with its rear. The front car of the moving train (1079) was telescoped by the rear car of the standing train (5066),[195] and passengers were trapped. Nine people died and more than 70 were injured, dozens of whom were described as "walking wounded".[196] Red Line service was suspended between the Fort Totten and Takoma stations, and New Hampshire Avenue was closed.[197][198] One of the dead was the operator of the train that collided with the stopped train.

On November 29, 2009, at 4:27 am, two trains collided at the West Falls Church train yard. One train pulled in and collided with the back of the other train. No customers were aboard, and only minor injuries to the operators and cleaning staff were reported. However, three cars (1106, 1171, and 3216) were believed to be damaged beyond repair.[199]

Derailments

[edit]

On January 13, 1982, a train derailed at a malfunctioning crossover switch south of the Federal Triangle station. In attempting to restore the train to the rails, supervisors failed to notice that another car had also derailed. The other rail car slid off the track and hit a tunnel support, killing three people and injuring 25 in its first fatal crash. Coincidentally, this crash occurred about 30 minutes after Air Florida Flight 90 crashed into the nearby 14th Street Bridge during a major snowstorm.[6]

On January 20, 2003, during construction of a new canopy at the National Airport station, Metro began running trains through the center track even though it had not been constructed for standard operations, and a Blue Line train derailed at the switch. No injuries resulted but the crash delayed construction by a number of weeks.[200]

On January 7, 2007, a Green Line train carrying approximately 120 people derailed near the Mount Vernon Square station in downtown Washington. Trains were single-tracking at the time, and the derailment of the fifth car occurred where the train was switching from the south to northbound track. The crash injured at least 18 people and prompted the rescue of 60 people from a tunnel.[201] At least one person had a serious but non-life-threatening injury. The incident was one of a series of five derailments involving 5000-series cars, with four of those occurring on side tracks and not involving passengers.[202]

On June 9, 2008, an Orange Line train (2000-series) derailed between the Rosslyn and Court House stations.[203][204]

On March 27, 2009, a Red Line train derailed just before 4:30 pm just south of Bethesda station causing delays but no injuries. A second train was sent to move the first train but it too derailed when it was about 600 feet (180 m) from the first train.[205]

On February 12, 2010, a Red Line train derailed at about 10:13 am as it left the Farragut North station in downtown Washington. After leaving the station, the train entered the pocket track north of the station. As it continued, an automatic derailer at the end of the pocket track intentionally derailed the train as a safety measure. If the train had continued moving forward on the pocket track, it would have entered the path of an oncoming train. The wheels of the first two cars in the six-car, White-Flint-bound train were forced off the tracks, stopping the train. Almost all of the estimated 345 passengers were evacuated from the damaged train by 11:50 am and the NTSB arrived on the scene by noon. Two minor injuries were reported, and a third passenger was taken to George Washington University Hospital.[206] The NTSB ruled the crash was due to the train operator's failure to follow standard procedures and WMATA management for failure to provide proper supervision of the train operator which resulted in the incomplete configuration of the train identification and destination codes leading to the routing of the train into the pocket track.[207]

On April 24, 2012, around 7:15 pm, a Blue Line train bound for Franconia–Springfield derailed near Rosslyn. No injuries were reported.[208]

On July 6, 2012, around 4:45 pm, a Green Line train bound for downtown Washington, D.C., and Branch Avenue derailed near West Hyattsville. No injuries were reported. A heat kink, due to the hot weather, was identified as the probable cause of the accident.[209]

On August 6, 2015, a non-passenger train derailed outside the Smithsonian station. The track condition that caused the derailment had been detected a month earlier but was not repaired.[210]

On July 29, 2016, a Silver Line train heading in the direction of Wiehle–Reston East station derailed outside East Falls Church station. Service was suspended between Ballston and West Falls Church and McLean stations on the Orange and Silver Lines.[211]

On September 1, 2016, Metro announced the derailment of an empty six-car train in the Alexandria Rail Yard. No injuries or service interruptions were reported and an investigation is ongoing.[212]

On January 15, 2018, a Red Line train derailed between the Farragut North and Metro Center stations. No injuries were reported. This was the first derailment of the new 7000-series trains.[213]

On July 7, 2020, a 7000-series Red line train derailed one wheelset on departure from Silver Spring around 11:20 in the morning.

On October 12, 2021, a 7000-series Blue Line train derailed outside the Arlington Cemetery station. This forced the evacuation of all 187 passengers on board with no reported injuries.[214] Cause of the derailment was initially stated to be an axle not up to specifications and resulted in sidelining the entire 7000-series fleet of trains, approximately 60% of WMATA's current trains through Friday, October 29, 2021, for further inspection.[215] On October 28, 2021, WMATA announced that the system would continue running at a reduced capacity through November 15, 2021, as further investigation took place.[214] The inspection determined a defect causes the car's wheels to be pushed outward. As of July 2022, the system was still running without most 7000-series cars. Workers manually inspect wheels on eight trains daily to catch the defect before it becomes problematic; the remaining cars are out of service pending an automated fix.[216]

Safety measures

[edit]On July 13, 2009, WMATA adopted a "zero tolerance" policy for train or bus operators found to be texting or using other hand-held devices while on the job. This new and stricter policy came after investigations of several mass-transit accidents in the U.S. found that operators were texting at the time of the accident. The policy change was announced the day after a passenger of a Metro train videotaped the operator texting while operating the train.[217]

Smoke incidents

[edit]During the early evening rush on January 12, 2015, a Yellow Line train stopped in the tunnel. It filled with smoke just after departing L'Enfant Plaza for Pentagon due to "an electrical arcing event" ahead in the tunnel. Everyone on board was evacuated; 84 people were taken to hospitals, and one died.[218]

On March 14, 2016, an electrified rail caught fire between McPherson Square and Farragut West, causing significant disruptions on the Blue, Orange, and Silver lines. Two days later, the entire Metro system was shut down so its electric rail power grid could be inspected.[219]

Future expansion

[edit]As of 2008, WMATA expects an average of one million riders daily by 2030. The need to increase capacity has renewed plans to add 220 cars to the system and reroute trains to alleviate congestion at the busiest stations.[220] Population growth in the region has also revived efforts to extend service, build new stations, and construct additional lines.

Planned or proposed projects

[edit]Line extensions

[edit]The original plan called for ten future extensions on top of the core system. The Red Line would have been extended from the Rockville station northwest to Germantown, Maryland. The Green Line would have been lengthened northward from Greenbelt to Laurel, Maryland, and southward from Branch Avenue to Brandywine, Maryland. The Blue Line initially consisted of a southwestern branch to Backlick Road and Burke, Virginia, which was never built. The Orange Line would have extended westward through Northern Virginia past the Vienna station to Centreville or Haymarket, and northeastward past New Carrollton to Bowie, Maryland. Alternatively, the Blue Line would have been extended east past Downtown Largo to Bowie. The future Silver Line was also included in this proposal.[17]

In 2001, officials considered realigning the Blue Line between Rosslyn and Stadium–Armory stations by building a bridge or tunnel from Virginia to a new station in Georgetown. Blue Line trains share a single tunnel with Orange Line and Silver Line trains to cross the Potomac River. The current tunnel limits service in each direction, creating a choke point.[221] The proposal was later rejected due to cost,[222] but Metro again started considering a similar scenario in 2011.[223]

In 2005 the Department of Defense announced that it would be shifting 18,000 jobs to Fort Belvoir in Virginia and at least 5,000 jobs to Fort Meade in Maryland by 2012, as part of that year's Base Realignment and Closure plan. In anticipation of such a move, local officials and the military proposed extending the Blue and Green Lines to service each base. The proposed extension of the Green Line could cost $100 million per mile ($60 million per kilometer), and a light rail extension to Fort Belvoir was estimated to cost up to $800 million. Neither proposal has established timelines for planning or construction.[224][225]

The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) announced on January 18, 2008, that it and the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT) had begun work on a draft environmental impact statement (EIS) for the I-66 corridor in Fairfax and Prince William counties. According to VDOT the EIS, officially named the I-66 Multimodal Transportation and Environment Study, would focus on improving mobility along I-66 from the Capital Beltway (I-495) interchange in Fairfax County to the interchange with U.S. Route 15 in Prince William County. The EIS also allegedly includes a four-station extension of the Orange Line past Vienna. The extension would continue to run in the I-66 median and would have stations at Chain Bridge Road, Fair Oaks, Stringfellow Road and Centreville near Virginia Route 28 and U.S. Route 29.[226] In its final report published June 8, 2012, the study and analysis revealed that an "extension would have a minimal impact on Metrorail ridership and volumes on study area roadways inside the Beltway and would therefore not relieve congestion in the study corridor."[227]

In 2011 Metro began studying the needs of the system through 2040. WMATA subsequently published a study on the alternatives, none of which were funded for planning or construction.[223][228] New Metro rail lines and extensions under consideration as part of this long-term plan included:

- a new Loop line which parallels the Capital Beltway, known as the "Beltway Line"[228]: 7

- a new Brown Line from the Friendship Heights station to White Oak, Maryland, which would pass through the District and Silver Spring, running parallel to the Red Line.[228]: 6

- rerouting the Yellow Line to either a new alignment, or a new tunnel parallel to the Green Line, in the District north of the Potomac River[228]: 4

- a 5-station spur of the Green Line to National Harbor in Maryland[228]: 9

- re-routing the Blue or Silver Lines in the District and/or building a separate express route for the Silver Line in Virginia[228]: 5

- extensions to existing lines, including:[228]: 8–9

- Red Line northwest to Metropolitan Grove (2 stations)

- Orange Line east to Bowie (3 stations) or west to Centreville or Gainesville (3 or 5 stations, respectively)

- Yellow Line south to Lorton (8 stations)

- Green Line northeast to BWI Airport (6 stations) or southeast to White Plains (6 stations)

- Blue Line east to Bowie (5 stations) or southwest to Potomac Mills (4 stations)

- Silver Line northwest to Leesburg (3 stations)

- four inter-line connections to allow greater service flexibility[228]: 10

- several infill stations on existing lines[228]: 11

In September 2021, a report on the capacity improvements of Blue/Orange/Silver lines proposed four alternative extensions for the system:

- Converting the Blue Line into a circle line, extending it to National Harbor and Alexandria.[229] The proposed extension starts from a new station at Rosslyn, continues to Georgetown through a new tunnel under the Potomac River, then runs under M Street NE, just north of the existing Blue/Orange/Silver central segment, and connects to the Red Line at Union Station. It then turns south towards Buzzard Point, Joint Base Anacostia–Bolling, and National Harbor and crosses the Woodrow Wilson Bridge to Alexandria. The loop rejoins the current system at Huntington on the current Yellow Line, which is re-routed to Franconia–Springfield.[230][231]

- A Blue Line extension to Greenbelt, which would follow a similar route through Georgetown to Union Station, then turn north towards Union Market and Ivy City before connecting with the Green Line at Greenbelt.[230]

- A Silver Line Express service from West Falls Church to Rosslyn with a similar route Greenbelt as the previous alternative.

- A Silver Line extension to New Carrollton.

All four alternatives use the same central segment layout from Rosslyn to Union Station through Georgetown.[230] NBC4 Washington further reported on the proposed loop in December 2022. At the time, there was a crowding problem at the Rosslyn station, and this expansion could be the solution to solve this crowding problem. A final design was published in July 2023.[232]

Individual and infill stations

[edit]Before construction on Metro began, a proposed station was put forward for the Kennedy Center. Congress had already approved the construction of a station on the Orange/Blue/Silver Lines at 23rd and H Streets, near George Washington University, at the site of what is now Foggy Bottom station. According to a Washington Post article from February 1966, rerouting the line to accommodate a station under the center would cost an estimated $12.3 million.[233] The National Capital Transportation Agency's administrator at the time, Walter J. McCarter, suggested that the Center "may wish to enhance the relationship to the station by constructing a pleasant, above-ground walkway from the station to the Center," referring to the then soon-to-be-built Foggy Bottom station. Rep. William B. Widnall, Republican of New Jersey, used it as an opportunity to push for moving the center to a central, downtown location.[234]

The 2011 Metro transit-needs study identified five additional sites where infill stations could be built. These included Kansas Avenue and Montgomery College on the Red Line, respectively in Northwest D.C. and Rockville, Maryland; Oklahoma Avenue on the Blue, Orange, and Silver Lines near the D.C. Armory in Northeast D.C.; Eisenhower Valley on the Blue Line in Alexandria, Virginia; and the St. Elizabeths Hospital campus on the Green Line in Southeast D.C.[228]: 11

Related non-WMATA projects

[edit]

A number of light rail and urban streetcar projects are under construction or have been proposed to extend or supplement service provided by Metro. The Purple Line, a light rail system, operated by the Maryland Transit Administration, is under construction as of 2024 and is scheduled to open in late 2027.[235][better source needed] The project was originally envisioned as a circular heavy rail line connecting the outer stations on each branch of the Metrorail system, in a pattern roughly mirroring the Capital Beltway.[236] The current project will run between the Bethesda and New Carrollton stations by way of Silver Spring and College Park. The Purple Line will connect both branches of the Red Line to the Green and Orange Lines, and would decrease the travel time between suburban Metro stations.[235][237]

The Corridor Cities Transitway (CCT) is a proposed 15-mile (24 km) bus rapid transit line that would link Clarksburg, Maryland, in northern Montgomery County with the Shady Grove station on the Red Line.[238] Assuming that the anticipated federal, state, and local government funds are provided, construction of the first 9 miles (14 km) of the system would begin in 2018.[239]

In 2005, a Maryland lawmaker proposed a light rail system to connect areas of Southern Maryland, especially the rapidly growing area around the town of Waldorf, to the Branch Avenue station on the Green Line.[240]

The District of Columbia Department of Transportation is building the new DC Streetcar system to improve transit connectivity within the District. A tram line to connect Bolling Air Force Base to the Anacostia station and was originally expected to open in 2010. Streetcar routes have been proposed in the Atlas District, Capitol Hill, and the K Street corridor.[241] After seven years of construction, the Atlas District route, known as the H/Benning Street route, opened on February 27, 2016.[242]

In 2013, the Georgetown Business Improvement District proposed a gondola lift between Georgetown and Rosslyn as an alternative to placing a Metro stop at Georgetown in its 2013–2028 economic plans.[243] Washington, D.C., and Arlington County have been conducting feasibility studies for it since 2016.[243]

In media

[edit]

The Washington Metro has often appeared in movies and television shows set in Washington. However, due to fees and expenses required to film in the Metro, scenes of the Metro in film are often not of the Metro itself, but of other stand-in subway stations that are made to represent the Metro.[244]

The vaulted ceilings of the Metro have become a cultural signifier of Washington, D.C., and are often seen in photographs and other art depicting the city.[245]

See also

[edit]- List of metro systems

- Transportation in Washington, D.C.

- United States Capitol Subway System

- Architecture of Washington, D.C.

References

[edit]- ^ "Transit Ridership Report Third Quarter 2024" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. November 20, 2024. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ "Transit Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2023" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. March 4, 2024. Retrieved September 5, 2024.

- ^ a b "WMATA Summary – Level Rail Car Performance For Design And Simulation" (PDF). Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. October 13, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 9, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ Schrag, Zachary (2006). "Introduction". The Great Society Subway: A History of the Washington Metro. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-8018-8246-X.Google Books search/preview Archived November 18, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Questions & Answers About Metro". Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. 2017. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

What do I need to know to build near Metro property? Metro reviews designs and monitors construction of projects adjacent to Metrorail and Metrobus property...

- ^ a b c d "History". Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. 2017. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ "Metro launches Silver Line, largest expansion of region's rail system in more than two decades" (Press release). Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. July 25, 2014. Archived from the original on June 18, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ a b "Metro Facts 2018" (PDF). WMATA. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ "With soaring Metro, DC Streetcar, and VRE ridership, Washington region leads transit recovery in US". Greater Greater Washington. July 6, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ a b "215 million people rode Metro in fiscal year 2008". Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. July 8, 2008. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ "Harland Bartholomew: His Contributions to American Urban Planning" (PDF). American Planning Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 25, 2009. Retrieved November 22, 2006.

- ^ Schrag, Zachary (2006). The Great Society Subway: A History of the Washington Metro. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8246-X.

- ^ Pub. L. 86–669, H.R. 11135, 74 Stat. 537, enacted July 14, 1960

- ^ Schrag, Zachary M. "Planning: The Adopted Regional System, 1966–1968". Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved August 17, 2006.

- ^ Pub. L. 89–774, S. 3488, 80 Stat. 1324, enacted November 6, 1966

- ^ "WMATA's Metro Proposal from 1967". June 19, 2016.

- ^ a b "Subway System for Washington And Its Suburbs Wins Approval" (PDF). The New York Times. March 2, 1968. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ M, Aaron (June 25, 2012). "Metro's 17-Foot Long "Experimental Station"". Ghosts of DC. Archived from the original on February 23, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Eisen, Jack (December 10, 1969). "Ground Is Broken On Metro, Job Let: Earth Is Turned On Metro, Job Let". The Washington Post. p. 1. ProQuest 143602416.

- ^ Eisen, Jack (March 28, 1976). "Metro Opens: Crowds Stall Some Trains". The Washington Post. p. 1. ProQuest 146502708.

- ^ "Washington metro opens". Railway Gazette International. May 1976. p. 163.