Ahmad ibn Fadlan

Ahmad ibn Fadlan | |

|---|---|

| Born | |

| Theological work | |

| Era | Islamic golden age |

| Main interests | Islamic jurisprudence |

Ahmad ibn Fadlan ibn al-Abbas al-Baghdadi (Arabic: أحمد بن فضلان بن العباس بن راشد بن حماد, romanized: Aḥmad ibn Faḍlān ibn al-ʿAbbās al-Baghdādī) was a 10th-century traveler from Baghdad, Abbasid Caliphate,[a] famous for his account of his travels as a member of an embassy of the Abbasid caliph, al-Muqtadir of Baghdad, to the king of the Volga Bulgars, known as his [[[:wikt:رسالة#Arabic|risāla]]] Error: {{Transliteration}}: transliteration text not Latin script (pos 9) (help) ("account" or "journal").[b]

His account is most notable for providing a detailed description of the Volga Vikings, including eyewitness accounts of life as part of a trade caravan and witnessing a ship burial.[4] He also notably described the lifestyle of the Oghuz Turks while the Khazaria, Cumans, and Pechenegs were still around.[5]

Ibn Fadlan's detailed writings have been cited by numerous historians. They have also inspired entertainment works, including Michael Crichton's novel Eaters of the Dead and its film adaptation The 13th Warrior.[6]

Biography

[edit]

Background

[edit]Ahmad ibn Fadlan was described as an Arab in contemporaneous sources.[2][3] However, the Encyclopedia of Islam and Richard N. Frye add that nothing can be said with certainty about his origin, his ethnicity, his education, or even the dates of his birth and death.[8][2]

Primary source documents and historical texts show that Ahmad Ibn Fadlan was a faqih, an expert in Islamic jurisprudence and faith, in the court of the Abbasid Caliph al-Muqtadir.[9] It appears certain from his writing that prior to his departure on his historic mission, he had already been serving for some time in the court of al-Muqtadir. Other than the fact that he was both a traveler and a theologian in service of the Abbasid Caliphate, little is known about Ahmad Ibn Fadlan prior to 921 and his self-reported travels.

The embassy

[edit]

Ibn Fadlan was sent from Baghdad in 921 to serve as the secretary to an ambassador from the Abbasid Caliph al-Muqtadir to the iltäbär (vassal-king under the Khazars) of the Volga Bulgaria, Almış.

On 21 June 921 (11 safar AH 309), a diplomatic party led by Susan al-Rassi, a eunuch in the caliph's court, left Baghdad.[10] Primarily, the purpose of their mission was to explain Islamic law to the recently converted Bulgar peoples living on the eastern bank of the Volga River in what is now Russia. Additionally, the embassy was sent in response to a request by the king of the Volga Bulgars to help them against their enemies, the Khazars.[11] Ibn Fadlan served as the group's religious advisor and lead counselor for Islamic religious doctrine and law.[12]

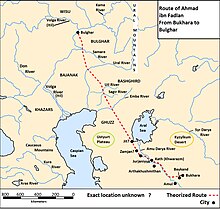

Ahmad Ibn Fadlan and the diplomatic party utilized established caravan routes toward Bukhara, now part of Uzbekistan, but instead of following that route all the way to the east, they turned northward in what is now northeastern Iran. Leaving the city of Gurgan near the Caspian Sea, they crossed lands belonging to a variety of Turkic peoples, notably the Khazar Khaganate, Oghuz Turks on the east coast of the Caspian, the Pechenegs on the Ural River and the Bashkirs in what is now central Russia, but the largest portion of his account is dedicated to the Rus, i.e. the Varangians (Vikings)[citation needed] on the Volga trade route. All told, the delegation covered some 4000 kilometers (2500 mi).[10]

Ibn Fadlan's envoy reached the Volga Bulgar capital on 12 May 922 (12 muharram AH 310). When they arrived, Ibn Fadlan read aloud a letter from the caliph to the Bulgar Khan and presented him with gifts from the caliphate. At the meeting with the Bulgar ruler, Ibn Fadlan delivered the caliph's letter, but was criticized for not bringing with him the promised money from the caliph to build a fortress as defense against enemies of the Bulgars.[13]

Ethnographic writing

[edit]Manuscript tradition

[edit]For a long time, only an incomplete version of the account was known, transmitted as quotations in the geographical dictionary of Yāqūt (under the headings Atil, Bashgird, Bulghār, Khazar, Khwārizm, Rūs),[14] published in 1823 by Christian Martin Frähn.[15]

Only in 1923 was a manuscript discovered by Zeki Velidi Togan in the Astane Quds Museum, Mashhad, Iran.[11] The manuscript, Razawi Library MS 5229, dates from the 13th century (7th century Hijra) and consists of 420 pages (210 folia). Besides other geographical treatises, it contains a fuller version of Ibn Fadlan's text (pp. 390–420). Additional passages not preserved in MS 5229 are quoted in the work of the 16th century Persian geographer Amīn Rāzī called Haft Iqlīm ("Seven Climes").

Neither source seems to record Ibn Fadlān's complete report. Yāqūt offers excerpts and several times claims that Ibn Fadlān also recounted his return to Bagdad, but does not quote such material. Meanwhile, the text in Razawi Library MS 5229 breaks off part way through describing the Khazars.[16]

Account of the Volga Bulgars

[edit]One noteworthy aspect of the Volga Bulgars that Ibn Fadlan focused on was their religion and the institution of Islam in these territories. The Bulgar king had invited religious instruction as a gesture of homage to the Abbasids in exchange for financial and military support, and Ibn Fadlan's mission as a faqih was one of proselytization as well as diplomacy.[17]

For example, Ibn Fadlan details in his encounter that the Volga Bulgar Khan commits an error in his prayer exhortations by repeating the prayer twice. One scholar calls it an "illuminating episode" in the text where Ibn Fadlan expresses his great anger and disgust over the fact that the Khan and the Volga Bulgars in general are practicing some form of imperfect and doctrinally unsound Islam. In general, Ibn Fadlan recognized and judged the peoples of central Eurasia he encountered by the possession and practice of Islam, along with their efforts put forth to utilize, implement, and foster Islamic faith and social practice in their respective society. Consequently, many of the peoples and societies to Ibn Fadlan were "like asses gone astray. They have no religious bonds with God, nor do they have recourse to reason".[18]

I have seen the Rus as they came on their merchant journeys and encamped by the Itil. I have never seen more perfect physical specimens, tall as date palms, blond and ruddy; they wear neither tunics nor kaftans, but the men wear a garment which covers one side of the body and leaves a hand free. Each man has an axe, a sword, and a knife, and keeps each by him at all times. Each woman wears on either breast a box of iron, silver, copper, or gold; the value of the box indicates the wealth of the husband. Each box has a ring from which depends a knife. The women wear neck-rings of gold and silver. Their most prized ornaments are green glass beads. They string them as necklaces for their women.

Account of the Rus'

[edit]A substantial portion of Ibn Fadlan's account is dedicated to the description of a people he called the Rūs (روس) or Rūsiyyah. Though the identification of the people Ibn Fadlān describes is uncertain,[19] they are generally assumed to be Volga Vikings; the traders were likely of Scandinavian origin while their crews also included Finns, Slavs, and others.[20] The Rūs appear as traders who set up shop on the river banks nearby the Bolğar camp. They are described as having bodies tall as (date) palm trees, with blond hair and ruddy skin. Each is tattooed from "the tips of his toes to his neck" with dark blue or dark green "designs" and all men are armed with an axe, sword, and long knife.[21]

Ibn Fadlan describes the Rus as perfect physical specimens and the hygiene of the Rūsiyyah as disgusting and shameless, especially regarding to sex (which they perform openly even in groups), and considers them vulgar and unsophisticated. In that, his account contrasts with that of the Persian traveler Ibn Rustah, whose impressions of the Rus were more favorable, although it has been attributed to a possibly intentional mistranslation with the original texts being more in line with Ibn Fadlan's narrative.[22] He also describes in great detail the funeral of one of their chieftains (a ship burial involving human sacrifice).[23] Some scholars believe that it took place in the modern Balymer complex.[24]

They are the filthiest of all Allah’s creatures: they do not purify themselves after excreting or urinating or wash themselves when in a state of ritual impurity after coitus and do not even wash their hands after food.

— Ibn Fadlan, [25]

Editions and translations

[edit](In chronological order)

- Ibn Faḍlān, Aḥmad; Frähn, Christian Martin (1823). Ibn Foszląn's und anderer Araber Berichte über die Russen älterer Zeit. Text und Übersetzung mit kritisch-philologischen Ammerkungen. Nebst drei Breilagen über sogenannte Russen-Stämme und Kiew, die Warenger und das Warenger-Meer, und das Land Wisu, ebenfalls nach arabischen Schriftstellern (in German). Saint-Petersburg: aus der Buchdruckerei der Akademie. OCLC 457333793.

- Togan, Ahmed Zeki Velidi (1939). Ibn Fadlan's Reisebericht (in German). Leipzig: Kommissionsverlag F. A. Brockhaus. [from Razawi Library MS 5229]

- Kovalevskii, A. P. (1956). Kniga Akhmeda Ibn-Fadlana o ego Puteschestvii na Volgu 921-922 gg (in Russian). Kharkov. [Includes photographic reproduction of Razawi Library MS 5229.]

- Canard, Marius (1958). "La relation du voyage d'Ibn Fadlân chez les Bulgares de la Volga". Annales de l'Institut d'Etudes Orientales de l'Université d'Alger (in French). pp. 41–116.

- Dahhan, S. (1959). Risālat Ibn Fadlān. Damascus: al-Jāmi‘ al-‘Ilmī al-‘Arabī.

- McKeithen, James E. (1979). The Risalah of Ibn Fadlan: An Annotated Translation with Introduction.

- Ibn-Faḍlān, Ahmad (1988). Ibn Fadlân, Voyage chez les Bulgares de la Volga (in French). Translated by Canard, Marius; Miquel, Andre. Paris: Sindbad. OCLC 255663160. [French translation, including additions to the text of Razawi Library MS 5229 from Yāqūt's quotations.]

- al-Faqih, Ibn; Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad; Aḥmad Ibn Faḍlān; Misʻar Ibn Muhalhil Abū Dulaf al-Khazrajī; Fuat Sezgin; M. Amawi; A. Jokhosha; E. Neubauer (1987). Collection of Geographical Works: Reproduced from MS 5229 Riḍawīya Library, Mashhad. Frankfurt am Main: I. H. A. I. S. at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University. OCLC 469349123.

- Бораджиева, Л.-М.; Наумов, Г. (1992). Ibn Fadlan - Index Ибн Фадлан, Пътешествие до Волжска (in Bulgarian). България ИК "Аргес", София.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Flowers, Stephen E. (1998). Ibn Fadlan's Travel-Report: As It Concerns the Scandinavian Rüs. Smithville, TX: Rûna-Raven. OCLC 496024366.

- Montgomery, James E. (2000). "Ibn Faḍlān and the Rūsiyyah". Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies. 3: 1–25. doi:10.5617/jais.4553. [Translates the section on the Rūsiyyah.]

- Frye, Richard N. (2005). Ibn Fadlan's Journey to Russia: A Tenth-Century Traveler from Baghdad to the Volga River. Princeton: Marcus Weiner Publishers.

- Simon, Róbert (2007). Ibn Fadlán: Beszámoló a volgai bolgárok földjén tett utazásról. Budapest: Corvina Kiadó.

- Ibn Fadlan and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers in the Far North. Translated by Lunde, Paul; Stone, Caroline E.M. Penguin Classics. 2011. ISBN 978-0140455076.

- Aḥmad ibn Faḍlān, Mission to the Volga, trans. by James E. Montgomery (New York: New York University Press, 2017), ISBN 9781479899890

- Ibn Faḍlān, Ahmad (2018). Viagem ao Volga (in Brazilian Portuguese). Translated by Criado, Pedro Martins. São Paulo: Carambaia. ISBN 978-85-69002-40-6.

Appearances in popular culture

[edit]Ahmad Ibn Fadlān is a major character in Michael Crichton's 1976 novel Eaters of the Dead, which draws heavily on Ibn Fadlān's writings in its opening passages. In the 1999 film adaptation of the novel, The 13th Warrior, Ibn Fadlān is played by Antonio Banderas.[26]

Ibn Fadlān's journey is also the subject of the 2007 Syrian TV series Saqf al-Alam.

Samirah "Sam" al-Abbas, a main character from Magnus Chase and the Gods of Asgard, as well as her betrothed, Amir Fadlan, are said to be descendants of Ahmad ibn Fadlan.

In the 2003 anime Planetes, the body of an astronaut named Ibn Fadlan was buried in a metal coffin by being sent to the depths of space. However, although he says that he belongs to space, he somehow returned to his world environment and was perceived as space debris. Like Ibn Fadlan as a real-life voyager, the retired astronaut says something important.[vague]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Very little is known about Ibn Fadlan other than what can be inferred from his risāla. He is usually assumed to have been ethnically Arab, although there is no positive evidence to this effect.[1][2][3]

- ^ The full title is Risālat Ibn Faḍlān, mab‘ūth al-khalīfah al-‘Abbāsī al-Muqtadir ilá bilād Ṣiqālīyah, ‘an riḥlatihi ... fī al-qarn al-‘āshir al-Mīlādī (رسـالـة ابن فـضـلان، مـبـعـوث الـخـلـيـفـة الـعـبـاسـي الـمـقـتـدر إلـى بـلاد الـصـقـالـيـة، عـن رحـلـتـه ... في الـقـرن الـعـاشـر الـمـيـلادي) or ma šahidat fi baladi-t-turk wa al-ẖazar wa ar-rus wa aṣ-ṣaqalibat wa al-bašġird wa ġirham ("Account of the lands of the Turks, the Khazars, the Rus, the Saqaliba [i.e. Slavs] and the Bashkirs")

References

[edit]- ^ Knight 2001, pp. 32–34.

- ^ a b c Frye 2005, p. 8.

- ^ a b Lunde & Stone 2011, p. xiii.

- ^ Perry 2009: "...left a unique geo-historical and ethnographic record of the northern fringes of 10th-century Eurasia." See also Gabriel 1999, pp. 36–42.

- ^ Curta, Florin (2019). Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages (500-1300) (2 Vols). Boston: BRILL. p. 152. ISBN 978-90-04-39519-0. OCLC 1111434007.

- ^ "Saudi Aramco World : Among the Norse Tribes: The Remarkable Account of Ibn Fadlan". archive.aramcoworld.com. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- ^ Kovalevskii, A. P., Kniga Akhmeda Ibn-Fadlana o ego Puteschestvii na Volgu 921-922 gg (Kharkov, 1956), p. 345.

- ^ Zadeh 2017.

- ^ Gabriel 1999, p. 36-42.

- ^ a b Knight 2001, p. 81-82.

- ^ a b Hermes 2012, pp. 80–84.

- ^ Knight 2001, p. 32-34.

- ^ Frye 2005[page needed], Hermes 2012, pp. 80–98

- ^ Lunde & Stone 2011, p. xxxiv-xxxv.

- ^ Ibn Faḍlān & Frähn 1823.

- ^ Lunde & Stone 2011, p. xxxv-xxxvi.

- ^ Hermes 2012: "...what was ultimately sought by Almish had more to do with politics and money than with spirituality and religion. As a growing number of scholars have observed, there seemed to be a political agreement between the Bulghar king and the Abbasid caliph. With this arrangement, the former would receive financial and military help in exchange for paying religious-political homage to the Abbasids."

- ^ Perry 2009, p. 159–60.

- ^ Montgomery 2000.

- ^ Wilson, Joseph Daniel (Spring 2014). "Black banner and white nights: The world of Ibn Fadlan". JMU Scholarly Commons.

- ^ Lunde & Stone 2011, p. 45-46.

- ^ "See footnote 35". www.vostlit.info. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- ^ Lunde & Stone 2011, p. 45-54.

- ^ (in Russian) Сибирский курьер. Тайны древнего кургана

- ^ Jakobsen, Hanne (2013-07-17). "Old Arabic texts describe dirty Vikings". www.sciencenorway.no. Retrieved 2023-11-29.

- ^ Lunde & Stone 2011, p. xxxi and xxxiii (quoting xxxiii n. 16).

Sources

[edit]- Frye, Richard N. (2005). Ibn Fadlan's Journey to Russia: A Tenth-Century Traveler from Baghad to the Volga River. Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 978-1558763661.

- Gabriel, Judith (November–December 1999). "Among the Norse Tribes: The Remarkable Account of Ibn Fadlan". Saudi Aramco World. Vol. 50, no. 6. Houston: Aramco Services Company. pp. 36–42. Archived from the original on 2010-01-13. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- Hermes, Nizar F. (2012). "Utter Alterity or Pure Humanity: Barbarian Turks, Bulghars, and Rus (Vikings) in the Remarkable Risala of Ibn Fadlan". The (European) Other in Medieval Arabic Literature and Culture: Ninth-Twelfth Century AD. The New Middle Ages. New York: Palgrave.

- Knight, Judson (2001). "Ibn Fadlan: An Arab Among the Vikings of Russia". In Schlager, Neil; Lauer, Josh (eds.). Science and Its Times. Vol. 700 to 1449. Detroit: Gale.

- Lunde, Paul; Stone, Caroline E.M. (2011). Ibn Fadlan and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers in the Far North. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0140455076.

- Montgomery, James E. (2000). "Ibn Fadlan and the Rūsiyyah". Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies. 3: 1–25. doi:10.5617/jais.4553.

- Perry, John R. (2009). "Review of Frye (2005)". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 68 (2): 159–160. doi:10.1086/604698. ISSN 1545-6978. JSTOR 10.1086/604698.

- Zadeh, Travis (2017). "Ibn Faḍlān". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_30766. ISSN 1873-9830.

External links

[edit]- 9th-century Arab people

- 10th-century Arab people

- 10th-century businesspeople

- 10th-century people from the Abbasid Caliphate

- 10th-century travelers

- 10th-century writers

- Explorers of Asia

- Explorers of Europe

- Geographers from the Abbasid Caliphate

- Travel writers of the medieval Islamic world

- Writers from Baghdad

- Foreign relations of the Abbasid Caliphate